PART 2: The Clinical Framing of Obesity

Tomaquag “Belonging(s)” Blog

March 2016 Part II

Belonging(s) “A close relationship among a group and personal or public effects”

“Kunoopeam” (Welcome)!

This Belonging(s) Blog is a continuation of a three-part series by student Esmeralda Lopez. Ms. Lopez’s blog is the result of an assignment from her class “Treaty Rights and Food Fights: Eating Local in Indian Country”. The course, taught by Elizabeth M. Hoover, PhD., Assistant Professor of American and Ethnic Studies explores the disparate health conditions faced by Native communities and the efforts by many groups to address these health problems through increasing community access to traditional food, whether by gardening projects or a revival of hunting and fishing traditions…”

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by Guest Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of the Tomaquag Museum or any employee thereof. Tomaquag Museum is not responsible for the accuracy of any of the information supplied by Guest Bloggers.

As a recap, Part I titled Food as Medicine explores an alternate Nutrition Model based on a combination of traditional and contemporary foods. In part II, Ms. Lopez discusses an issue related to the Body Mass Index model or BMI.

Part II Badly Made Indicator (BMI) of Health

The clinical framing of obesity

One of the objectives of the blog post Food as Medicine was to introduce a Native nutrition model that was developed “to teach nutrition while preserving cultural knowledge and traditional food systems” (Conti 235).

Our ancestors didn’t have nutritional guidelines/models/pyramids, so why is there a need for them now? Is it because of the global “obesity epidemic”? If so, what’s responsible for the increasing incidence of obesity?

Before we can examine public health research and literature on nutrition transition that seeks to provide an explanation, we must know how obesity is framed. Charles E. Rosenberg historian of medicine and Professor of History of Science and Medicine at Harvard said, "In some ways disease does not exist until we have agreed that it does, by perceiving, naming, and responding to it" (xiiv). A disease first has to be framed before it is diagnosable. In other words, a disease isn’t a black and white biological event but an agreed upon biological and social phenomenon. To truly understand the framing of obesity we need to know how it is constructed in biology and society.

The body mass index (BMI) is used globally by healthcare providers for identifying patients as either ‘normal’, ’overweight’ or ’obese’. The BMI is widely used in both clinical practice and research studies. One might think that because research studies use BMI, the clinical tool must be accurate. Sadly, this “sophisticated” tool only needs height and weight measurements to calculate BMI! This reductionist approach does not take into account varying body composition. In The Daily Mail (an online news publication in the UK) published an article this July about the impracticality of using the BMI.

In 2013, BBC News published the article “British Asians set lower BMI target”, the purpose of the article was to discuss why Asians and other minority groups should aim for a lower BMI of 23 rather than 25. The Diabetes UK organization says it's a step away from the BMI's “one size fits all” approach. In acknowledging that the BMI does not work for “all”, the article is implicitly saying that the tool was designed for the white body. For example, the article says, "People from black and other minority groups would most likely also benefit from having a BMI less than 23, but should aim for a BMI at least lower than 25". This recommendation to minority ethnic groups is based on solely on the greater number of minorities with chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers. Whether they intended to or not, they reduced the causation of complex chronic diseases to simply the result of excess body fat, thereby stigmatizing and racializing the obesity problem.

Thinking critically on the information being presented, it is evident that the BMI was not created for “the Asian body” and “other bodies of color”. I used the term “Asian body” in quotes because there isn’t a “quintessential Asian body” as the article implies. People can argue that the BMI doesn’t accurately measure white bodies either. While this is true, it does not deny the fact that the BMI was designed (with sample population measurements) for white bodies, who are not asked in the article to aim for a lower BMI or linked to the comorbidity of excess body fat and chronic diseases (type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers).

The continued use of BMI in clinical practice and health research is both impractical and detrimental to communities of color. Its widespread use “legitimizes” it as an accurate assessment of health such that, many of us (myself included) have used it to assess our health. Just to clarify, I’m not advocating for the creation of BMIs tailored for communities of color. Rather I’m advocating for a shift away from “one-size fits all” diagnostic tools of health to a more comprehensive assessment of health. Before this can happen everyone (not just communities of color) must question both the ethics and accuracy of “one-size fits all” diagnostic tools of health.

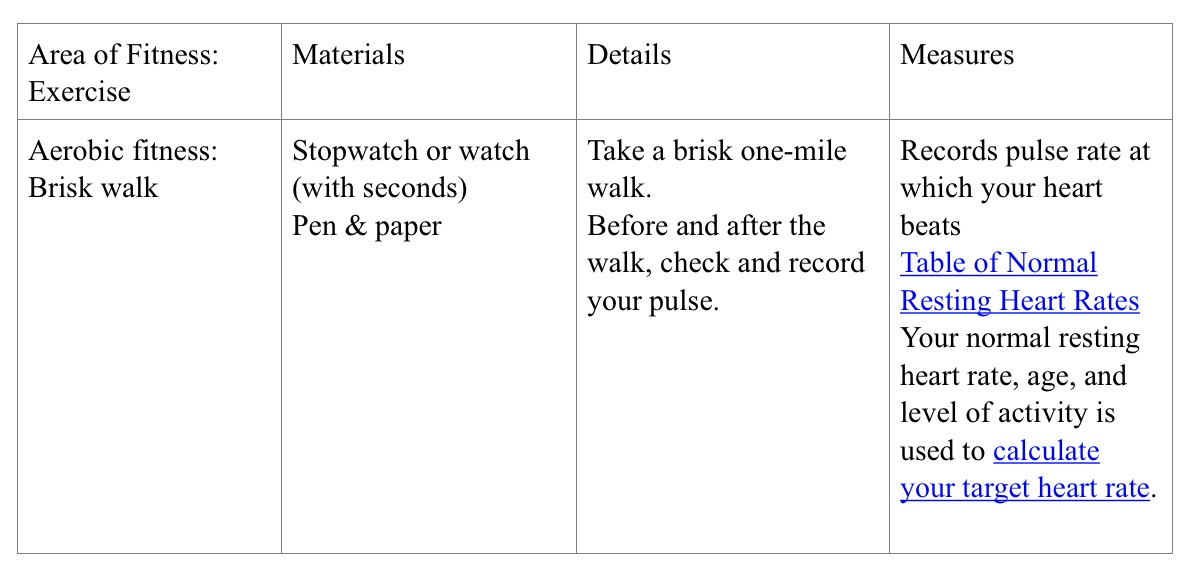

A few ways we can assess our health is through fitness exercises, a great resource is an article by the Mayo Clinic. There are three key areas of fitness: aerobic fitness, muscular strength, and endurance, flexibility. Material you will need for the fitness exercises are a watch/stopwatch, a cloth measuring tape, a yardstick, heavy duty tape, scale and a someone to help record your scores. I have included a summary table of the fitness exercises and provided hyperlinks to other useful tools.

References:

Conti, K. 2006. "Diabetes Prevention in Indian Country: Developing Nutrition Models to Tell the Story of the Food-System Change." Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 17(3):234-245

Charles Rosenberg, “Framing disease,” Framing Disease: Studies in Cultural History. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992.

Kutaputush (Thank You) and may the fresh air and sunshine invigorate you!

Kim Peters, Collections Manager

The Tomaquag “Belonging(s)” Blog, is a monthly conversation dedicated to the happenings, musings of staff, and a peek at the collections of the Tomaquag Museum. We welcome guest bloggers, and topics relevant to Native American Museums and Indian Country, especially those located in the New England area.

If you are interested in contributing to our blog please contact kpeters@tomaquagmuseum.org Please visit us at www.tomaquagmuseum.org. and like us on Facebook.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by Guest Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of the Tomaquag Museum or any employee thereof. Tomaquag Museum is not responsible for the accuracy of any of the information supplied by Guest Bloggers.

HAVE YOU HEARD ABOUT OUR PODCAST?