Reenactments: We remember and We remind

Asco wequassunnúmmis readers! Chrystal Mars Baker (Narragansett/Niantic), Education Manager at Tomaquag Museum here again with a bit of history and thoughts to share on the subject of reenactments! I hope this encourages more critical thought while you consider the message sharing this intends to evoke. I embarked upon a journey to learn about my forebears through research about the early Sachems, or Chiefs, of the Narragansetts and Niantics hoping to find writings particularly about our Saunksquûaog, or female Sachems (Saunksquûaog is the plural and Saunks, is the singular). Very little is written about our Saunksquûaog and their significance amongst our tribes as the writings of colonial documents were mainly recorded through a patriarchal lens. So additionally, I asked my Elders, who are the keepers of our history.

Esther Ninigret, daughter of Sachem George Ninigret, granddaughter of Sachem Ninigret II and sister of Thomas Ninigret (aka “King Tom”) was born during the time when English names and surnames were being given to or adopted by many of the Narragansett and Niantic peoples. As of this writing I have not yet been able to uncover Ester’s traditional names. In 1770, Esther became Saunks of the combined Narragansett and Niantic peoples and was the last to be recognized through traditional ceremony. A head piece (crown) made of wampumpeag (white shell beads) and suquahog (the deep/dark coloring which identifies this clam) was placed upon her head, strands of these beads draped around her neck along with other adornments signifying her position as leader. It is also recorded that she was accompanied by 20 of her guards where she was elevated upon the “rock” and there were around 500 people in attendance.

Photo Courtesy of Chrystal Mars Baker

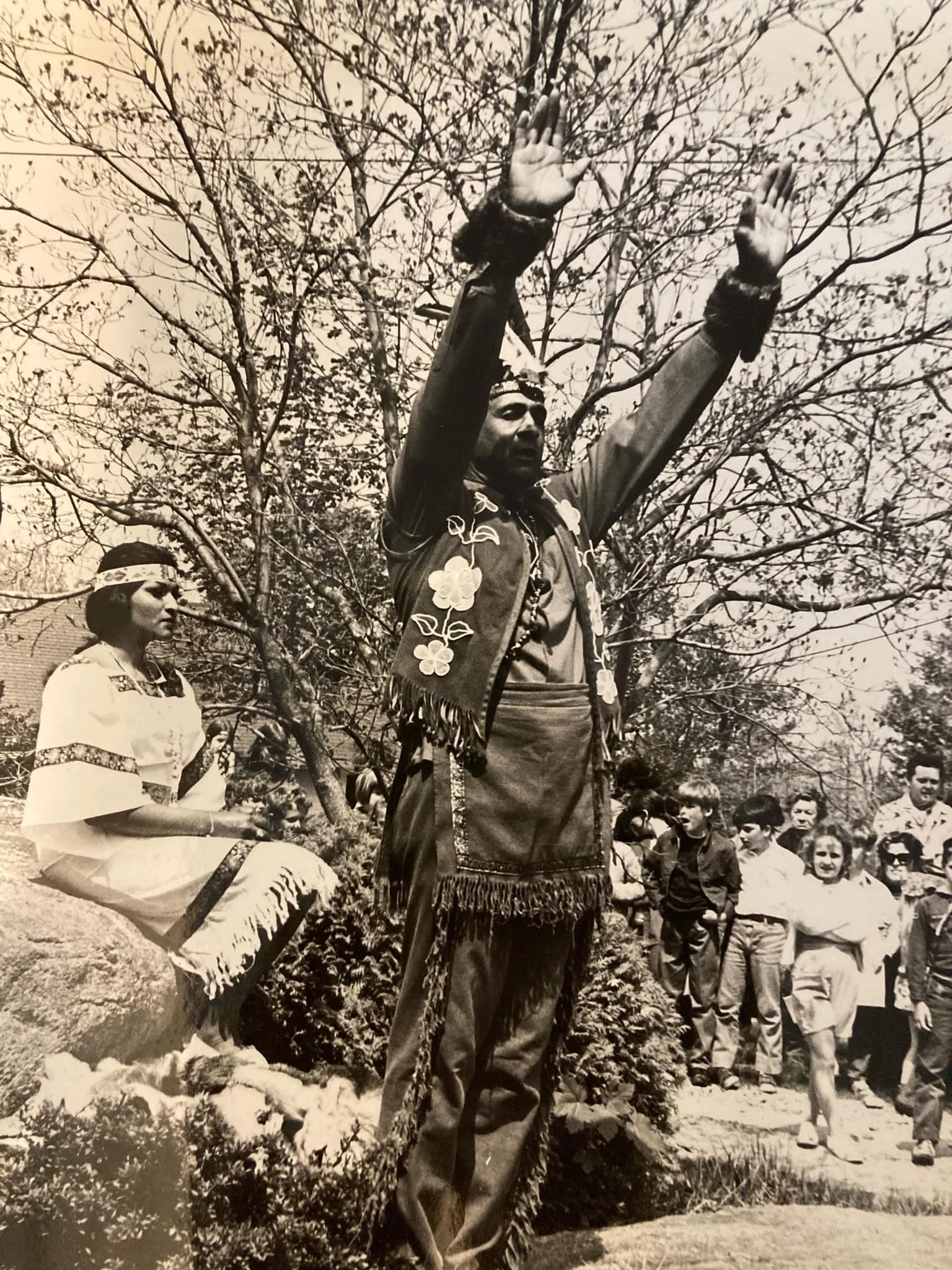

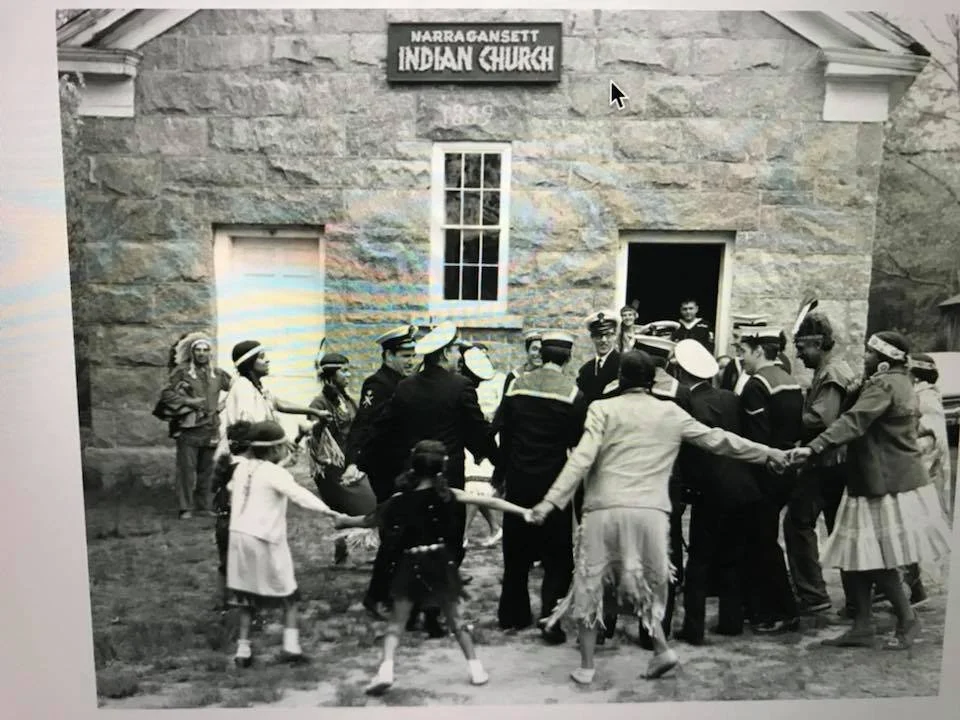

On May 16, 1970 (according to Red Wing) around 700 people attended a reenactment of the coronation of Esther which took place at what is known as “King Tom” Farm located in Charlestown, Rhode Island. I recently visited the “Coronation Rock” where I found inscribed into it those very words. The rock is not easily seen from the road and perhaps very few even know of its existence as it sits behind a very large dwelling where once stood the original home of Thomas Ninigret. This particular piece of property has a dubious and unscrupulous history as to how the lands were obtained from the Narragansetts as does most of the lands of the Narragansetts. But I digress. Planning and organizing the reenactment was done by members of the Sons and Daughters of First Americans (SDFA) an Indigenous only organization founded in 1938 by Elias Brown, Miss Ruth Brown, Ruth Brown, George Hazard, Ernest Hazard, Nettie Davis, George Davis, Theodore Brown, Christopher Noka, Theodore Glasko, Daniel Congdon (Sagamore Chief White Oak That Bends-Mohegan) and Mary Ella Congdon (Red Wing). Also among the planners and researchers of this historic event were Tall Oak (Everett Weeden), Como Netop (Rev. Harold Mars Sr.) and Red Earth (Laura Fry Mars), the latter two being founding members of the Charlestown Historical Society in 1968. In addition, the reenactment performers were many tribal members including me at the tender age of not quite two years old! Queen Esther was played by my beloved maternal aunt, Red Doe (Diana Spears Mars), and my paternal grandfather Rev. Harold Mars Sr. was the Tribal Prophet who performed the ceremony. All of these wonderful collaborators have since returned to Creator. However, Diana, “Queen Esther,” shared this voice-recorded memory at the age of 84 and which I will forever treasure. I hope as you hear her voice and read this blog, you will feel the strength of endurance and continuation! (*On April 11, 2023 a month after the recording, my beloved aunt passed from this life, so I publish this blog in honor of her memory.)

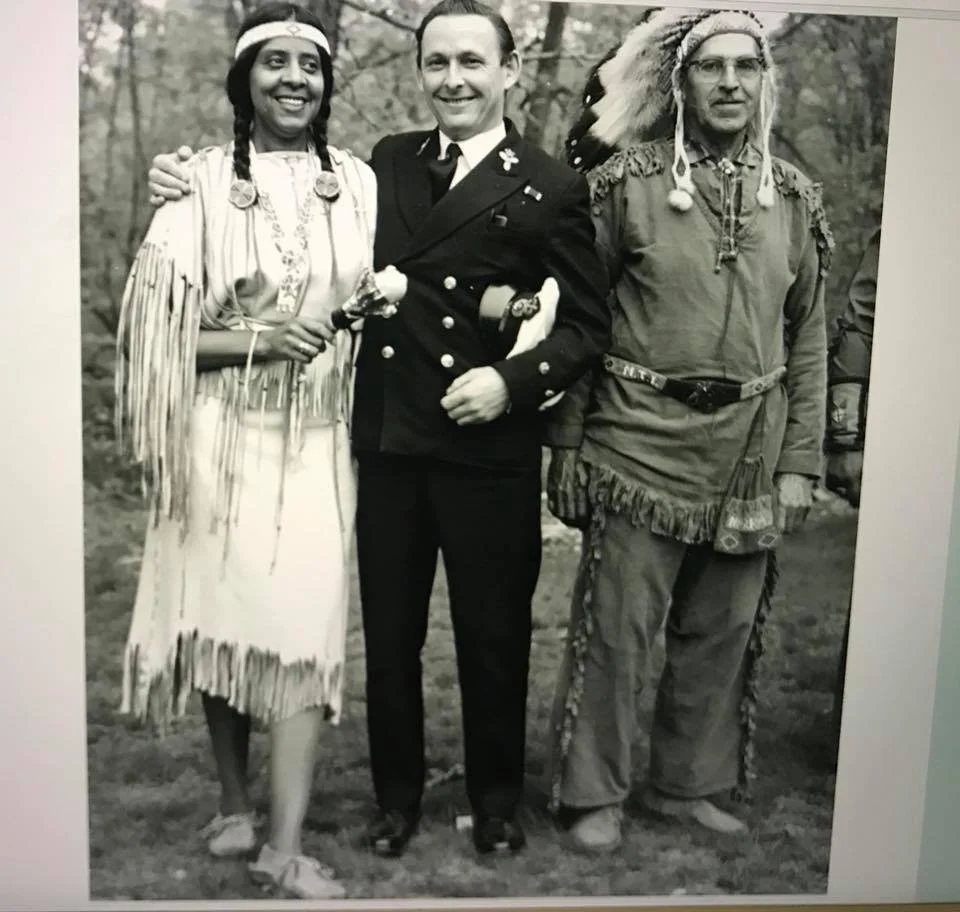

Here are a few photographs of the participants of that day in 1970. Among the many Narragansetts who participated, Diana recalled that Tall Oak invited the Boy Scouts and English Navy personnel who were stationed at Quonset to be part of the program!

Diana Spears Mars (front), Everett Tall Oak Weeden (Rt), and his wife, Patricia Weeden holding son Christopher Taupauwau Weeden (Lt); Photo courtesy of Starr Spears Mars

Rev. Harold C. Mars Sr., Narragansett Tribal Prophet (Front); Photo courtesy of Charlestown Historical Society

Photo courtesy of Charlestown Historical Society

Photo courtesy of Charlestown Historical Society

Alberta Laughing Water Stanton Wilcox, Narragansett (Lt), Unknown Navy Personnel (middle), Chief Sachem George Red Fox Watson (Rt); Photo courtesy of Charlestown Historical Society

Photo courtesy of Charlestown Historical Society

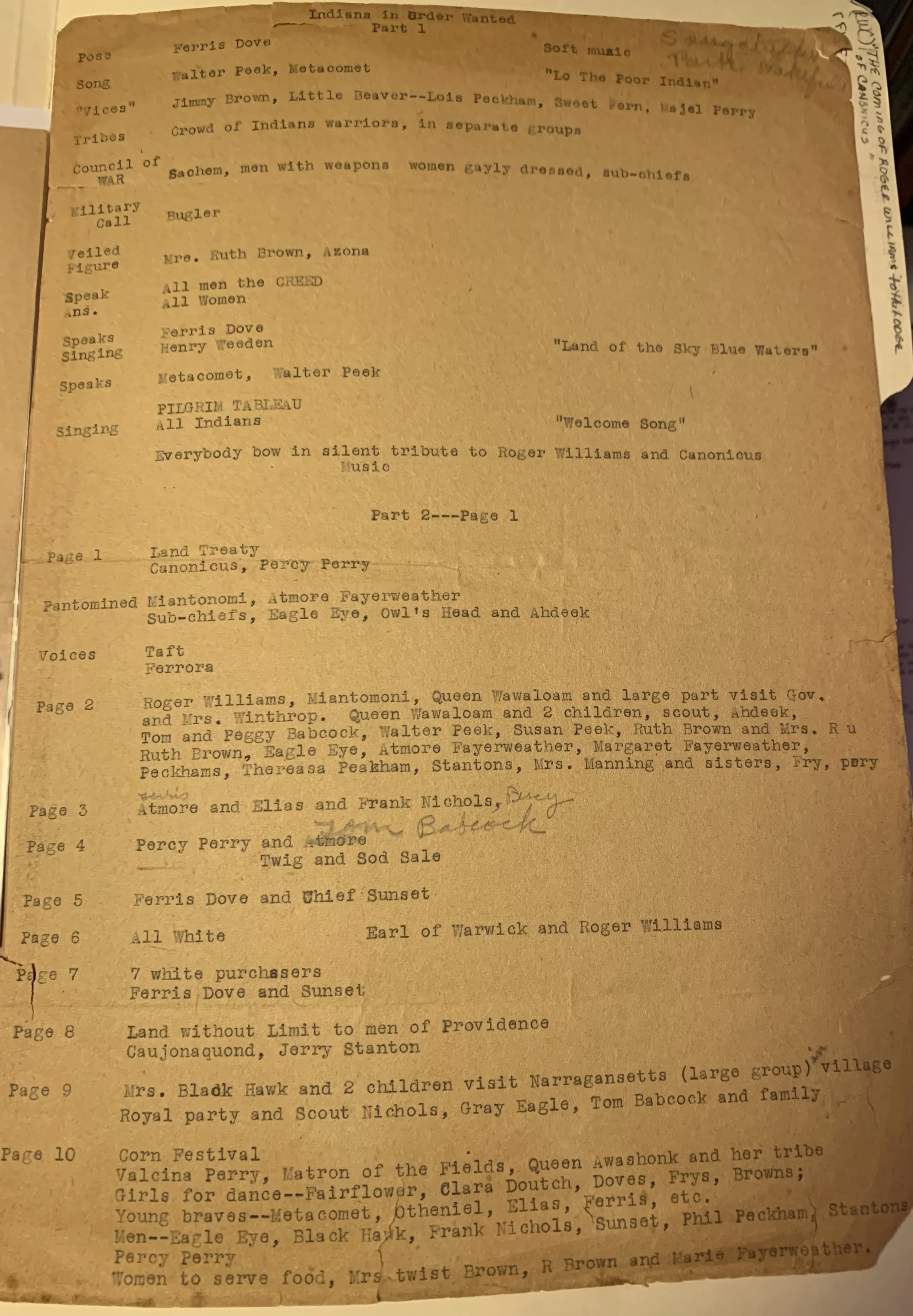

While searching through Tomaquag’s archives for more information, I came across another reenactment which drew me into further study. This reenactment was written in 1938 and portrayed the coming of Roger Williams to the lodge of Canonicus, Sachem of the Narragansetts in the 1630s. There are so many questions about whether Roger Williams was a “friend” to the Narragansetts, in particular to Canonicus. While the debate continues for many, I have drawn my own conclusions. You may do your research and draw your own. But keep in mind, that since the arrival of Roger Williams along with those who followed after him to the shores of Narragansett territory, the Narragansetts diminished in numbers from ~10,000 people and the most powerful tribe of the region to ~300 as recorded in 1675. The annihilation taking place within the short span of 40 years following colonial settlement to the massacre at Great Swamp.

Edward Chief Sun Set Michaels (lt); pilgrim; Frank Chief Grey Eagle Nichols (Rt); Tomaquag Museum Archives

Cast List.. Tomaquag Museum Archives

Why are these Indigenous, historical reenactments hundreds of years after the actual events so significant? Because they bring history alive and make an indelible impression on our minds. Learning through a variety of mediums is essential and as there are no photographs of the actual events from our ancient past, reenactments allow us to visualize as well as hear the voices from the past. It is not a celebration of the tragedy of history, it is an acknowledgement of its truth in another form. Let me first state that reenactments of Native people’s history by non-Native peoples is not what these reenactments that I have written about were. The reenactments in this submission are both written and performed by Native peoples sharing their own history. This, in my opinion, is appropriate.

What may be questioned is the reasoning and justifications that are rendered by those who choose to continue to portray history through reenactments using non-Indigenous participants, excluding Indigenous voice from the discussion of such reenactments before they are planned and enacted. Over the years reenactments have portrayed the heinous acts of genocide and murder of Indigenous peoples on their own homelands by the colonizers as a celebration of a particular battle giving way to the establishment of a place that has been recorded in history. I read several articles about this subject to try to understand the justification still being given in this 21st century when the truth of history should be learned and the voice of all involved in that history should be heard so that the atrocities of past history are shared responsibly and do not repeat themselves. But this is what I read from interviews with individuals representing their organizations such as those of the Westmoreland County Historical Society. The reenactment was of a public hanging of Mamachtaga, a Delaware Indian convicted of murder in 1785. Their spokesman, Scott Henry, said, “There was nothing malicious intended. We simply tried to accurately portray a case that was tried at Hanna’s Town.” Clearly upset over the calls he’d received from those opposing the reenactment, and in response to a letter of request by Chief Chester L. Brooks of the Delaware Tribe of Indians to remove the video from YouTube, Henry said, “One caller accused us of perpetuating a legacy of ethnic cleansing. This has all been blown out of proportion”. I understand his intent, however, I would ask why was this particular scene was necessary to be acted out in front of impressionable young viewers as well as adults perhaps not educated as to the entirety of the history behind the event being reenacted. It is important to educate the public about the entirety of historical events before choosing to reenact a short portion as it may be taken out of context.

In Oklahoma, a school district would stage Land Run reenactments as an educational tool for school children. The request to stop these reenactments generated this comment: “School board member Bob Hammack told NewsOK he thinks it’s a bad idea to stop the celebrations because the Land Run is a colorful and unique part of Oklahoma history. ‘This is political correctness run amok, promulgated by a handful of people who certainly don’t represent the vast majority of Oklahomans who are very proud of our history,’ Hammack said. ‘Any attempt to minimize what is a historical fact is flat-out wrong.’” To be fair, I am not from Oklahoma and so cannot speak to the Land Run history personally, however, as an Indigenous person who understands the history of land loss I agree with this response given by Lisa Snell, citizen of the Cherokee Nation, “‘American Indians aren’t chastising anyone to be “politically correct” – we are saying it is not acceptable to marginalize us. We are here, we matter, and most of all, our children matter and our history matters. Just as much as yours.’”

And lastly I share this quote from Alan Nunez in an article of August 15, 2022 where he wrote, “Native Americans historically have been mistreated, culturally appropriated, and been the subjects of many other offenses. Whether at the hands of the U.S. government, land conquerors, or just the people that live near them, it has been a longstanding issue that has been handled by giving back land and providing reparations, but ultimately, the relief has not changed much and the group is still one of the most vulnerable groups in the country. One of the more popular ways of culturally appropriating the group has been by way of battle reenactments. This also includes programs that portray the people.”

To this controversial subject I say, reenactments are useful when written by and portrayed by those peoples whose cultures are part of the story. I reiterate, all voices must be heard in the writing and planning as well as acting phases and all truth must be told. Consider first whether it is even necessary to portray historical events through reenactments to share lessons from history especially to impressionable young people. Instead, it may be more effective and appropriate to invite to your spaces those who have direct connections to the history you are sharing through conversation and open dialogue with all represented!