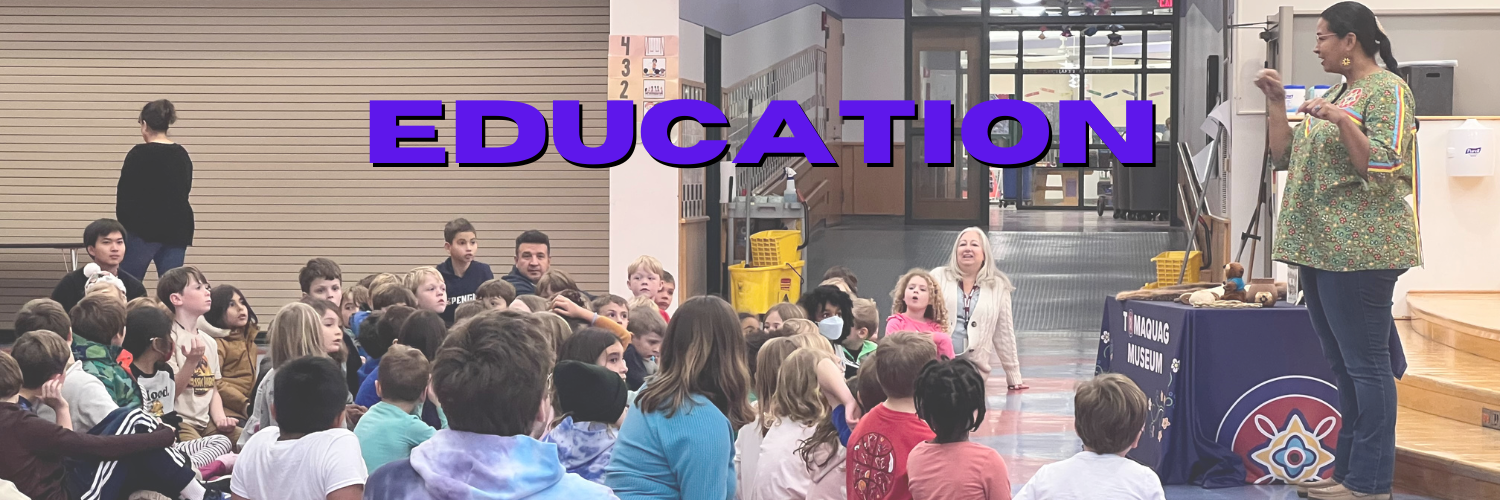

Tomaquag Museum Educators (left to right) Lorén M. Spears, Chrystal Mars Baker, Silvermoon LaRose, and Sararesa Hopkins.

Kunoopeam Netompaûog, Welcome Friends!

Tomaquag Museum welcomes you to learn with us! Learn more about Native communities of the Southern Dawnland (Southern New England) from our team of Indigenous educators. This education page has been curated with engaging resources and activities for all ages, just for you! So visit often as we will continue to update regularly.

Like what you see? Help us do more! Donate now to support our educational programming.

What’s Happening This Month?

Read “The Runner”

2026 (Quarter 1 Edition Title Here)

Watercolor Art courtesy of Mikaela Jackson, Piute (2025)

Want To Read More? Check Out Past Newsletters Listed by Topic to Aid In Your Research. Click Here To Explore

Watch Our Featured Video

Kid’s Corner:

Book of the Quarter:

“Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.”